The “The Nation’s Heart” series features a different country every week to highlight its current state of cardiac surgery, progress made, initiatives set, and prospects to come. Today, for the third blog of this series, Global Cardiac Surgery is featuring Vietnam, a lower-middle-income country in Southeast Asia with a long standing experience and leading example for cardiac surgery in the Region.

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, is the 15th most populous country in the world with almost 95 million people living in the vibrant, yet small country in Southeast Asia. After US forces left South Vietnam in 1973 and the US embargo was lifted in 1975, the country embarked on a painful process of recovery with reunification under a socialist government. Today, Vietnam has made important progress in political and economic sectors, but is trailing behind on education and health. Healthcare expenditure remains socialised and up to 70% of spending occurs through out-of-pocket payments by patients and their families.

In as early as 1958, the first heart surgery -a closed mitral commissurotomy on a 30-year-old man with rheumatic mitral stenosis- was performed by Professor Ton That Tung, setting the stage for many decades of cardiac surgical endeavours to come. In 1964, deep hypothermia was first used, followed by the cardiopulmonary bypass in 1965. In the years to come, most procedures, in particular surgery for congenital heart defects, were performed at US military hospitals in South Vietnam. After the US forces left the country, fewer than 10 open-heart surgeries were done each year, due to widespread lack of supplies, devices, trained personnel, and funding.

However, in 1992, the Carpentier Heart Institute (today: Vietnam Heart Institute) was founded in Ho Chi Min City (formerly Saigon) by the French cardiac surgeon Alain Carpentier. Today, the Vietnam Heart Institute is one of the biggest heart centers in Vietnam, performing over 1,000 open-heart surgeries each year and training entire cardiac teams for the country. In 2011, cardiac transplantation was initiated at the Third Military Hospital in Hanoi and in Hue, and in 2017 at Cho Ray Hospital. In addition, several centers are now performing minimally invasive aortic and mitral valve procedures with good results. Although most senior cardiac surgeons have received all or part of their formal and additional training abroad in France, Australia, or South Korea, to date, there are three approved government cardiothoracic surgery training programs in Vietnam, in Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh City, and one private at the Vietnam Heart Institute.

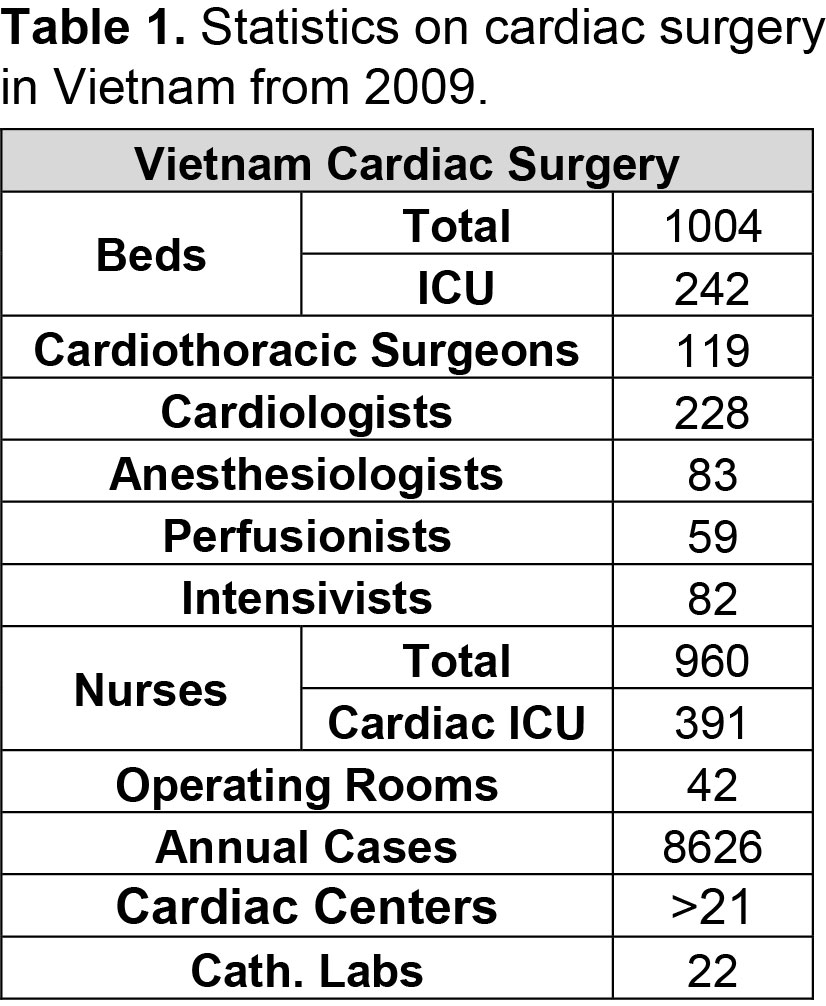

Currently, over 21 cardiac centers (of which 12 public) exist in Vietnam, covering a total of 119 cardiac surgeons and over 8,500 cardiac operations each year, yet only 4 of these perform more than 1,000 cases per year. Only 7 centers are able to perform neonatal and high-risk congenital heart surgery. Despite all efforts, the estimated backload of patients requiring cardiac care is as high as 80,000 cases. Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) and congenital heart disease (CHD) make up the bulk of cardiac conditions in Vietnam, responsible for more than 80% of cases. With a birth rate of almost 17 children per 1,000 people, close to 15,000 babies are born with CHD each year in Vietnam adding to the backload. Concurrently, although the government has put tremendous efforts in controlling rheumatic fever and thus rheumatic heart disease, over 5,000 adults wait for mitral valve surgery for RHD. Through attempting high case loads, costs are brought down to as comparably low as $1,500 for CHD surgery and $2,000 for valve surgery. Although the Vietnamese governments provides financial coverage of young patients to some extent, this program is inconsistent, and out-of-pocket payments for CHD patients average up to $500, which makes most families face catastrophic expenditure.

To bridge the unmet need for cardiac surgery and limit catastrophic expenditure, visiting international teams largely focus on treating CHD cases in Vietnam. However, increasing governmental funding for cardiac surgery programs and services, and foster support from and cooperation with private centers will prove fundamental to achieve a sustainable, efficient, and effective national model.

Published by